Parasites can have potential negative effects on beef cattle that can vary from subclinical immune suppression, irritation, annoyance, appetite suppression, and decreased production, to severe clinical disease and death. The management of parasites is a component of a preventive health program that should also include immunity management (vaccinations), management procedures, handling, and nutritional considerations that reflect an in-depth understanding of not only the beef production system but farm-specific issues and goals.

Internal Parasites

(trematodes) and protozoans (such as coccidia). Roundworms are considered the most economically important, and many programs revolve around their management. This section regarding internal parasites in beef cattle will focus around roundworms. Understanding the parasite life cycle and the level of parasite pressure is key to the management of internal parasites.

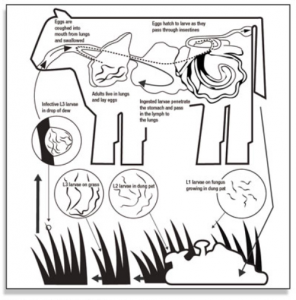

The following is the basic life cycle of internal (gastrointestinal) parasites in cattle:

1.Adult parasites live in the gastrointestinal tract of cattle and lay eggs that are shed in the manure.

2.When a parasite egg is shed on the pasture in the feces, this egg begins development, embryonating into a first stage larva (L1), then molting into a second stage larva (L2), and finally molting again into a third and infective stage larva (L3).

3.During the first two larval stages in the fecal pat, the larva are fairly immobile, feeding off the bacteria and other debris found in the feces.

4.During the third larval stage the larva move out of the fecal pat and onto nearby grass where they are consumed by cattle.

5.L3 larvae maintain an external sheath covering that provides extra protection from environmental conditions allowing survival during winter or drought conditions. This sheath prevents feeding, thus L3 larvae have a limited life span.

6.Egg development is greatly dependent upon temperature and moisture. Eggs that are passed in the middle of winter will not develop until warm weather returns in the spring. Eggs passed in the middle of a drought or other unfavorable conditions may develop into infective larvae in the feces but without moisture cannot move away from the pat where they can be consumed by a host animal when it eats grass. Eggs that are shed during favorable conditions can develop into infective larvae in just a few days if temperatures are warm and moisture is plentiful.

7.Once consumed by cattle, the infective larvae mature into adults over a period of 3-4 weeks (shorter in younger cattle, longer in adult cattle) and begin to lay eggs, which are shed onto pastures to start the cycle over again.

8.Some larvae can become inhibited or hypobiotic (go into hibernation) in the wall of the abomasum, sometimes referred to as L4 larvae. This process can occur during the winter in the north and in the summer in the south, with these larvae maturing and developing into adult worms when the environment for egg survival is more favorable.

Overall, the controlling of internal parasites has a significant positive return on investment for producers. The main focus of internal parasite control in beef cattle is roundworms. Diagnostics are needed to determine which specific worms are present. For beef cattle this is important because the roundworm life cycle depends on the shedding of the eggs on pasture, larvae development, and the ingestion of the larvae during grazing. Since much of beef cattle production depends on grazing of pastures, the management of roundworms is key. As long as cattle have access to grass, they will have an internal parasite challenge.

Control practices should consider the class (or age) of cattle, nutrition status, stress level, season, and likelihood of parasite contamination of the environment, and involve the use of pasture management options as well as the use of anthelmintic (dewormer) products for treatment.

Life-Cycle of Internal Parasites

Some pasture management activities may include leaving the pasture fallow, grazing other species, and dragging manure pats during the dry season to allow them to dry out.

Anthelmintics used to control internal parasites for beef cattle come in several forms including paste, injectable, drench, pour-on, bolus, and as a feed or mineral additive. Products have varying lengths of activity and costs, but fall into two main classes: benzimidazoles and macrocylic lactones. Benzimidazoles (white dewormers) available commercially contain albendazole, fenbendazole, or oxfendazole. Benzimidazoles are effective against most of the major adult gastrointestinal parasites and many of the larval stages. Products come in various oral formulations and have a short duration of efficacy. Macrocyclic lactones are the avermectins and milbemycins. Products in commercial use contain ivermectin, doramectin, eprinomectin, or moxidectin. The macrocyclic lactones have a potent, broad antiparasitic spectrum at low dose levels. They are active against many larval stages (including hypobiotic larvae) and are active against many external parasites as well. Products are available as oral, subcutaneous, and pour-on formulations for use in cattle. Duration of efficacy varies with the product and may be up to 35 days.

Approaches used to treat parasites in beef cattle are considered strategic deworming. This is the practice of treating cattle at times to not only get the benefit in that animal to prevent economic loss but also reduce environmental contamination for a period of time at least equal to the life cycle of the parasite removed.

Keys to strategic deworming are to place cattle that are not shedding eggs on pastures that are not infected; this is accomplished by deworming prior to spring turnout or fall treatment in the north (following killing frost). The benefit of treating in the fall is that cattle should be free of internal parasites all winter and going into the spring turnout (assuming an effective product was used). Cattle that go onto pasture at spring turnout are free of parasites, thus not shedding eggs, and will be consuming the infective larvae on the pasture if the pasture is contaminated. By consuming the infective larvae and not shedding new ones the cows will be reducing the load on the pasture (acting as vacuum cleaners). After a time the ingested infective larvae will mature and cows will start shedding eggs. Strategic deworming times the treatment so as to reduce the worm burden on the cattle and also decrease the parasite contamination of the pasture during the highest parasite period (spring/early summer).

The timing of these treatments can and should be timed with other management procedures such as summer vaccines for the calves and fall processing of calves and cows. Depending on the geographic location, such as in the south where the weather (moisture) is different, timings may be different, as well as the type of grazing program.

Calves and stockers should be considered within a strategic program while on a grazing program. Times of concern include prior to weaning while nursing the cow and while intensively grazing as a stocker. Calves should not be dewormed while being weaned. Preweaning treatment, prior to the stress of weaning, can reduce the potential negative impact on immune function as well as improve performance. Any time cattle are moving from pasture into a dry lot setting is a good time to deworm as this should clear cattle of parasite load for the time in the dry lot (similar to fall deworming) as there is no green grass to graze.

For the control of other types of internal parasites such as tapeworms (cestodes), flukes (trematodes), and protozoans (such as coccidia), similar concepts are applied. It is important to understand the different life cycles of these different types of parasites as well as the efficacy of products used to treat them.

External Parasites

The major external parasites that affect cattle include flies, grubs, lice, ticks, and mites. These external parasites feed on body tissues such as blood and skin, and in addition they cause irritation and discomfort that result in reduced weight gain and lost production. Parasites that take blood meals have the potential to serve as vectors for the transmission of diseases.

Horn Flies

Horn flies are blood-sucking flies that stay on the shoulders and backs of cattle almost continuously. A horn fly leaves the back of a cow or calf only to lay eggs in fresh manure. They take blood meals from the host 24 hours a day.

Face Flies

Face flies cluster on the faces of cattle and feed on secretions from the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and lips. Face flies do not suck blood. They do irritate the surface of the eyeball and may carry pathogens that contribute to pinkeye problems. They spend only a small portion of their life on cattle.

Stable Flies

Stable flies feed primarily on the legs and lower abdomen of cattle and take blood meals two to three times a day depending on the weather. After feeding they move to a resting place to digest the blood meal. Stable flies are associated with substantial economic loss in cattle from the blood loss and pain from feeding. As few as five flies per leg is economically significant in cattle.

Ticks

Ticks cause blood loss and discomfort, and can act as vectors for disease spread. High concentrations of ticks usually occur in brushy pastures and woodlands.

Lice

Lice that affect cattle are either of the biting or sucking type, and cause skin irritation and itching. The entire life cycle of lice is on the host and they are present year round but populations increase in winter months. Lice spread through contact with infested cattle. Infested cattle can experience reduced appetite and anemia, and appear unthrifty.

Mites

In cattle, mites can cause hair loss and a thickening of the skin. Infestation by mites is called mange. Mites are spread by close contact. Severe mange can weaken cattle and make them vulnerable to diseases. Certain types of mites are reportable.

Cattle Grubs (warbles)

Cattle grubs, or warbles, are the larval stage of the heel fly. The larvae migrate from the animal’s heel, where the eggs are deposited by the adult fly in early summer, to the back of the animal. The larvae can cause damage to the hide (due to the breathing hole they create) and if treated during the wrong time of the year can cause paralysis due to their location near the spinal column. Cattle should not be treated with a grubicide between November 15 and March 1 if cattle grubs are a concern.

Control of External Parasites

Control of external parasites usually revolves around the use of insecticides. These usually are a pyrethrin or an organophosphate. Strategies or combinations of strategies for delivery include: dust bags, back-rubbers (oilers), animal sprays, pour-ons, and insecticide impregnated ear tags. In addition, the use of injectable products or pour-ons with systemic activity work well to control lice and mites. Larvicides can also be part of control plan for certain types of flies as well as the use of predator wasps and environmental management. The use of dust bags and back-rubbers (oilers) can provide delivery of insecticides and economic fly control if located in an area that cattle are forced to move through such as a gateway or over a mineral feeder.

Post time: Jul-19-2022